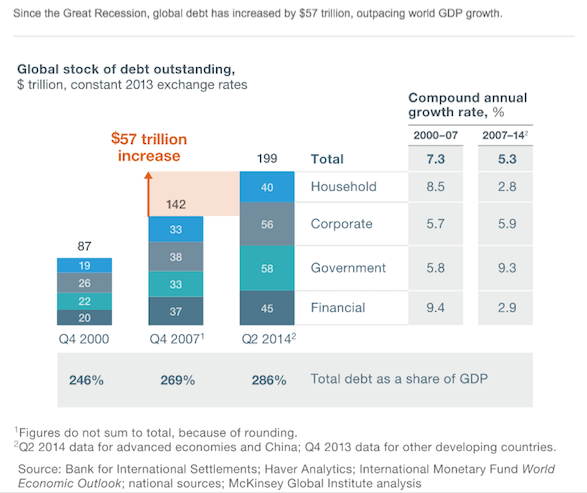

The last global financial meltdown has demonstrated that banks and other financial institutions are not simply private organisations; they provide a critically important public service – the flow of money through our interconnected market economies. Such regulation, to be effective, can only happen at the supranational level, since otherwise financial instruments will easily shift from one location to another and motivate governments to engage in a race to the bottom to attract them. Yet even newspapers friendly to the current practices of our financial system like the Financial Times and The Guardian report that we have learned little from the 2008 Collapse. Our banking and financial “professionals”, bailed out with taxpayers’ hard-earned money, have duly congratulated each other for surviving this “bump” and have returned to business as usual – to the very same practices and habits that brought the UK, Europe and the world to the brink of systemic financial meltdown. We are today more at risk than ever to witness a similar crisis to that of 2008 – and we are no better prepared than then to face it, let alone prevent it before it engulfs us once again with consequences far more dire than we have so far experienced. A McKinsey survey of debt across 47 countries rings a timely alarm bell and calls for fresh approaches to prevents such catastrophic events from recurring:“Overall debt relative to gross domestic product is now higher in most nations than it was before the [2008] crisis... Higher levels of debt pose questions about financial stability.”

As Joris Luyendijk, who spent two years, from 2011 to 2013, interviewing about 200 bankers and financial workers as part of an investigation into banking culture in the City of London after the crash aptly commented in an article worth being quoted at length:

“Although we did not quite fall off the edge after the crash in the way some bankers were anticipating, the painful effects are still being felt in almost every sector. At this distance, however, seven years on, it’s hard to see what has changed. And if nothing has changed, it could all happen again... The European commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, memorably said in 2013 that European politicians know very well what needs to be done to save the economy. They just don’t know how to get elected after doing it. A similar point could be made about the major parties in this country: they know very well what needs to be done to make finance safe again. They just don’t know where their campaign donations and second careers are going to come from once they have done it.

Still, the complicity of mainstream politicians is not the whole story. Finance today is global, while democratically legitimate politics operates on a national level. Banks can play off one country or block of countries against the other, threatening to pack up and leave if a piece of regulation should be introduced that doesn’t agree with them. And they do, shamelessly. “OK, let us assume our country takes on its financial sector,” a mainstream European politician told me. “In that case, our banks and financial firms simply move elsewhere, meaning we will have lost our voice in international forums. Meanwhile, globally, nothing has changed.” This then opens up the most difficult question of all: how is the global financial sector to be brought back under control if there is no global political authority capable of challenging it?"

Since 2008, many experts have drafted detailed proposals on how to “fix” the global financial system, by both conventional and less conventional means. But, as former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown, who had to manage the 2008 Financial Crisis during his tenure, aptly remarked regarding the management of the global economy, “…this global problem does not offer simple national solutions… [G]lobalization has thrust upon us shared problems we have to face in common together – and which in my view, cannot be resolved without coordinated action… The way forward is not to stop globalization in its tracks but to manage it better. And in a world economy that is growing more and more interdependent, this requires specific measures that add up to concerted international action of mutual benefit to all… Yet in the absence of a bigger vision of what can be achieved, the politics of each country inevitably pulls toward the narrow tasks and not the broad objectives…”

Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s This Time It’s Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly arrive at a similar conclusion based on a detailed study of the principal financial crises that have shaken our national and global economies since the mid-Eighteenth Century – that is, during the entirety of our current secular cycle, as they argue in favor of establishing “…a new independent international institution to help develop and enforce international financial regulations...”: “First, cross-border flows of capital continue to proliferate, often seeking light regulation as much as high rates of return. In order to have meaningful regulatory control over modern international financial behemoths, it is important to have some measure of coordination in financial regulation. Equally important, an international financial regulator can potentially provide some degree of political insulation from legislators who relentlessly lobby domestic regulators to ease up on regulatory rule and enforcement. Given that the specific qualifications needed to staff such an institution are extremely different from those prevalent in any of the current major multilateral lending institutions, we believe an entirely new institution is needed”.

It is therefore clear that a wide-ranging consensus has emerged among academics, professionals, and serious politicians that a safe, stable, secure and trustworthy financial system requires to be regulated and monitored by a supranational organisation, at the very least at the European level, if not at the Euro-Atlantic one, and that the UK's exit from the EU would lead to devastating consequences for both the British financial sector and its long-term economic prosperity.

The Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, who is also Chairman of the G20’s Financial Stability Board has repeatedly warned that Britain’s departure from the EU could have dangerous consequences on Britain’s financial stability and economic prosperity – and was immediately accused by Tory Eurosceptic grandees for making such inappropriate comments about a matter that supposedly did not concern him and his current mandate. The reality is that Carney, in his previous position as Governor of the Bank of Canada, was one of the few officials in a similar position to actively prevent his country’s financial meltdown in 2008 by working closely with the Canadian government to ensure that the Canadian financial system was resilient, well-regulated, and respectful of stated corporate ethnical principles and practices.

One of David Cameron’s key four demands in his negotiations with EU officials asks precisely for the City of London financial sector to be exempt from more stringent EU regulations and, to add insult to injury, to be given a veto over future decisions of the EU Euro-club to ensure that its decisions about the euro’s future will in no way endanger what he perceives as London’s leading position as the financial capital of Europe. It is very clear from this episode that what Cameron wants to achieve with such a demand is in no way or manner to render our financial system more resilient and safer for average citizens and the small businesses that constitute the backbone of British economic activity, but to allow City bankers to flout any possible institutional safeguards that would affect the positions, income, and power of his rich friends and party donors.

As Gordon Brown and David Carney both agree, Twenty-First Century financial problems can only be tackled in a sustainable and long-term manner by 21st Century, supranational institutions, at European and even Euro-Atlantic levels. It is imperative that we do not let ourselves be deluded by David Cameron’s claim that he is “fighting for Britain” in putting forward such demands in his negotiations with his EU partners. He is doing nothing of the sort- rather, he is simply defending the status quo and perks of the City of London’s financial fat-cats with million-pound Christmas bonuses, and the resulting donations such individuals and their organisations make to the Tory party to ensure it remains in power. Such is the truly incestuous relationship between City financiers and Westminster Tory politicians; we must unmask it for what it is, and debunk at all costs Cameron’s disingenuous and deliberately misleading claims of “fighting for Britain”.